Kahramanmaraş Survey

Data related to the monograph "The Kahramanmaraş Valley Survey: A Crossroads Along the Syro-Anatolian Frontier"

Project Abstract

An Overview of the Kahramanmaraş Survey

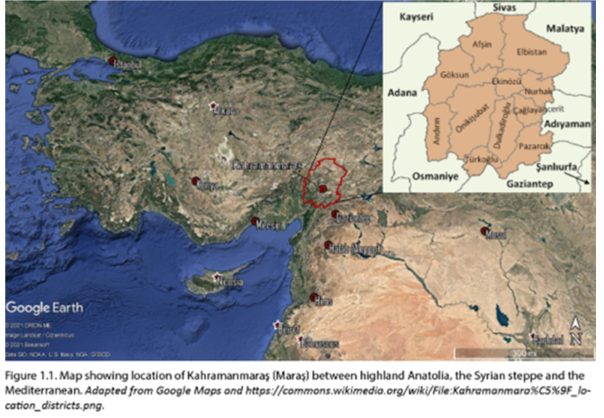

The Kahramanmaraş survey region lies in a cultural and geographic transition zone on the fringes of highland Anatolia and the Taurus Mountains to the north, the Mediterranean to the southwest and the Syro-Mesopotamian steppe to the southeast (figs. 1-2). The importance of the region lies in its location at the crossroads of the major lines of communication linking the highlands and lowlands on the western edge of the fertile crescent. The modern city of Kahramanmaraş (elevation 700-800 m) is located at the northern end of the fault-bounded “Hatay Graben” (the northern most extension of the Dead Sea fault) just east of the intersection of the Taurus and Amanus Mountains. Less than 10 km north of the city are high mountains rising more than 1800 m. that form a clear geographic boundary between the Taurus range and the lowland valley (elevation 500m) to the south. The Amanus mountains, famed in antiquity as sources of silver and wood, lie to the west of the plain and separate the area from Cilicia (modern Cukurova). To the east is the Kurt Dağ, an outlier of the Taurus Mountains, which parallels the Amanus Range and separates the region from the Euphrates River Drainage Basin.

The valley formed by the Aksu River, south of the modern city of Kahrmanmaraş, was the major focus of this research. The borderland location of the valley, its archaeological potential and a relatively complete historical record were factors that indicated a systematic regional survey would be productive. The goal of the research was to compile an archaeological overview, which would integrate environmental, historical and ethnohistorical studies of the valley in order to better understand the role that such meeting points, far from the centers of political power, played in the long-term cultural history of the region.

The original research design called for an examination of a larger territory, but practical considerations led us to focus our research on the valley to the south of the modern city of Kahramanmaraş and north of the border with Gaziantep province. The survey area is shaped like a “snow angel” with Kahramanmaraş as the head and the alluvial plains of the east-west flowing Erkenez and Aksu Rivers as the “wings.” To the south of the river valleys the foothills of the Amanus Range defined the western boundary of the survey area; only one valley system, the Yeşilyore, west of the modern town of Türkoğlu, was surveyed. The Kahramanmaraş-Gaziantep asphalt road formed the eastern boundary of the survey area (see Note 1, below) although we were able to survey north of the road west of the city. The southern edge was set at the provincial border between the Kahramanmaraş and Gaziantep province (see Note 2, below). Here the rocky outcrops of the Kurt Dağ approach the Amanus foothills, and the valley south of the Sağlık Göl is then less than 5 km. wide.

An Overview of the Data

The data presented here is the basis for the monograph, The Kahramanmaraş Valley Survey: A Crossroads Along the Syro-Anatolian Frontier, published by the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology (available for purchase from ISD). The primary data includes the records of the original 1993-1994 extensive survey, and records from an intensive survey around the site of KM 97, Domuztepe made by James E. Snead in 1995 (see Chapter 10 of the monograph). The forms and sketch maps from these sites (KM 228-240) as well as the records of sites identified by Lynn Swartz Dodd, Çiğdem Atakumen Eissenstat and local informants (KM 248-254) (Carter et al. 1999) are also presented here.

This information consists of the forms that were filled out at the time of the original collection and a sketch-map of the site. A site gazetteer compiled from these records, photos of the sites and photos of the sherd collections from numerous sites complete the basic data set. Subsequent to the original survey the sites were located on Google Earth and two files—one listing all sites in the order of their discovery (KM.kml) and one recording site type and period (Time Stamp.kml) are also presented here along with overlays of the original 1/25,000 survey maps and icons indicating site types. The data presented in the monograph devoted to the survey presents various interpretations, but it is hoped that in the future other views and additions to the record might be facilitated though open access to this information.

A Working Chronology for the Kahramanmaraş Region

The only absolute dates we have for the valley come from Domutepe, where excavated levels of the Halaf Period are dated by 14C to the first half of the sixth millennium B.C. The remainder of the long occupation sequence must be dated by the development of an internal ceramic chronology based on our surveys and comparanda from contemporary sites. Unfortunately few single period sites were identified although there were sites where cuts or land leveling brought relatively large homogeneous bodies of material to light.

The earliest occupation of the valley took place in the Middle Paleolithic (KM 43), but even this site appears to have later lithic assemblages on it (see Appendix 1). For this segment of the chronology we follow Garrard et al. 2004 and their work just to the south of ours in the Sakçegözü valley. A single epi-paleolithic and two possible PPNB sites represent the occupation of the region in the very early Neolithic.

In the Neolithic with the advent of ceramics we are able to compare the surface materials we found to the sequences identified in the Amuq, and in Sakçegözü (Du Platt Taylor et al. 1950) moreover enough sites were discovered to allow us to formulate a local chronological sequence spanning the 8-6th millennium. Earlier excavations in the Amuq (Braidwood and Braidwood 1960) and the resumption of excavations at Tell Kurdu (Özbal et al. 2004; Özbal 2011) and several other site in the region have yielded some absolute dates for the Halaf and Ubaid Period (Campbell 2007, Campbell and Fletcher 210). These dates overlap the Domuztepe dates and several fall within the Ubaid Period. In sum we have lumped Halaf and Ubaid together since distinguishing periods has proved difficult based on surface collections alone. For the Local Late Chalcolithic nearby Sakçegözü (Du Platt Taylor et al. 1950), Oylum Höyük (Özgen and Helwing 1999), the Amuq (Braidwood and Braidwood 1960), and the Euphrates sites such as Zeytinlibaçhe (Balossi-Restelli 2008), Haci Nebi (Pearce 2000) and Arslantepe (Fragipane 2000) offer well-dated comparative assemblages. More difficult to place is the EBA since Maraş. The publication of Gedikli Höyük (Duru 2010) along the resumption of work at Tilmen Hoyük (Duru 2003, Bonomo 2010), to the south have their own related, but nevertheless distinctive, ceramic assemblage.

Beginning with the Middle Bronze Age we have more difficulty in distinguishing the assemblages although they have parallels both on the plateau at Kültepe and in Syrian sites to the south. The later assemblage is close to that known for northern inner Syria as described by Nigro (2002). The contemporary ceramics from the plateau were identified on the basis of Arslatepe (Di Noccra 1993) and Kültepe (Kulakoğlu 2011). Dating Late Bronze and Early Iron Age assemblages proved even more problematic. Relatively recent excavation in the Amuq (Horowitz 2015) and the fortress of Taşlı Geçit, near Tilmen, (Benati 2013) have provided some well-dated comparative materials for the LBA and Early Iron Ages. Clear links to imperial Hittite ceramics, however, are only sporadically represented in our collections. The Early Iron Age (c. 1200-900 BCE) has some parallels with sites in the Amuq (e.g., Harrison 2013) or North Syria (Venturi 1998) but has been difficult to isolate in the Maraş survey collections. The reasons for this include a lack of a local plain ware sequence and easily identifiable painted wares similar to those known from the Amuq. For the Middle and Late Iron Ages we do not have the distinctive “Assyrian imperial fine wares” although the sequences from Tillehöyük (Blaylock 1999; Blaylock et al. ) and Tell Ahmar (Jamieson 2003) provide comparative materials for a number of undecorated buff wares.

The Maraş assemblage has numerous clear links with the Hellenistic-Late Roman assemblages. These are best illustrated in the assemblages from Lidarhöyük (Kazenwadel 1995), Jebel Khalid (Jackson and Tidmarsh 2011) and Zeugma (Kenrik 2009, 2013) all on the Euphrates.

The volume describes the assemblages from certain key sites and their comparisons upon which we base the regional ceramic chronology. A few of these are single period sites or, more often, sites with easily distinguishable and much later components. All had very rich surface collections which had parallels in sites across the valley and dated parallels from excavated sites in the region. The following table is meant then as a rough chronological guide to the long-term history of the Kahramanmaraş Valley subject to change when future controlled excavations take place in the region.

Notes:

Note 1: We were not given permission to work in the Pazarcık valley or south of the Kahramanmaraş provincial border, although both areas were included in our original survey permit application. Note also that the Adıyaman survey stops at Golbaşı (Blaylock et al. 1990).

Note 2: The border is particularly difficult to define on the ground and on the administrative maps at our disposal and so often we relied on the information provided by local residents, but just exactly where that boundary lay was often unclear and provided a lesson in the flexibility of borders.

References Cited

Balossi-Restelli, F. 2006. The local Late Chalcolithic (LC3) occupation at Zeytinli Bahçe (Birecik, Şanli-Urfa): the ceramic production. Anatolian Studies, 56, 17-46.

Blaylock, S. Iron Age Pottery from Tille Höyük, South-Eastern Turkey. In: Hausleiter, A. & Reiche, A., eds. Iron Age Pottery in Northern Mesopotamia, Northern Syria and South-Eastern Anatolia, 1999 Papers presented at the Meetings of the International "Table Ronde" Heidelberg (1995) and Niebrow (1997) and Other Contributions. 263-286: Ugarit Velag, 263-286.

Blaylock, S., D. Collon, M. Nesbitt, B. C. Coockson, S. Blaylock & T. Çakar 2016. Tille Höyük 3.2. The Iron Age: Pottery, Objects and Conclusions.

Bonomo, A. 2010. Middle Bronze Age II Pottery Assemblage. ICANNE.

Bonomo, A. 2010. Iron Age pottery assemblages in the Islahiye valley (Turkey). Poste, Rome, ICANNE.

Bonomo, A. 2011. La sequenza ceramica dell’area K5 sud a Tilmen Höyük: contesti e tipologie. In: S. Mazonni, F., Pecchioli Daddi, G. Torri, a D'agostino (ed.) Ricerche italiane in Anatolia: risultati delle attività sul campo per le Età del Bronzo e del Ferro (Studia Asiana 6),===. 31-46.Rome.

Braidwood, R. J. & L. S. Braidwood 1960. Excavations in the Plain of Antioch. Chicago.

Campbell, S. 2007. Rethinking Halaf Chronologies. Paléorient, 103-136.

Campbell, S. & A. Fletcher 2010. Questioning the Halaf-Ubaid Transition. In: Philip, R. C. a. G. (ed.) Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. 69-83.

Campbell, S. & E. Healey 2012. A ‘Well’and an Early Ceramic Neolithic Assemblage from Domuztepe. Neolithics, 11, 19-25.

Du Platt Taylor, J. & J. M. V. S. W. a. J. Waechter 1950. The Excavations at Sakce Gözü. Iraq, 12, 53-138.

Duru, R. 2003. Unutulmus bir baskent : Tilmen : İslâhiye bölgesi'inde 5400 yıllık bir yerleşmenin öyküsü = A forgotten capital city : Tilmen : the story of a 5400 year old settlement in the Islahiye Region, Southwest Anatolia. Istanbul.

Duru, R. 2010. Gedikli Karahöyük II : Prof. Dr. U. Bahadır Alkım’ın yönetiminde 1964-1967 yıllarında yapılan kazıların sonuçları = The results of excavations directed by Prof. Dr. U. Bahadır Alkım in the years 1964 - 1967. Ankara.

Frangipane, M. 2000. The Late Chalcolithic IEB I sequence at Arslantepe. Chronological and cultural remarks from a frontier site. In: Marro, C. (ed.) From the Euphrates to the Caucasus: Chronologies for the 4th-3rd millennium B.C.. 439-471.Istanbul.

Garrard, A., J. Conolly, J. Mcnabb & N. Moloney 2004. Palaeolithic-Neolithic Survey in the Sakçagözü Region of the North Levantine Rift Valley. In: Aurenche, O., Le MièRe, M. & Sanlaville, P. (eds.) From the river to the sea: the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic on the Euphrates and in the Northern Levant: studies in honour of Lorraine Copeland. 145-164.Oxford, England.

Harrison, T. 2013. Tayinat in the Early Iron Age. In: Yener, K. A. (ed.) Across the border: Late Bronze-Iron Age relations between Syria and Anatolia: proceedings of a symposium held at the Research Center of Anatolian Studies. 61-88.Leuven, Walpole Mass.

Jackson, H. & J. Tidmarsh 2011. Jebel Khalid on the Euphrates. The pottery. Sydney.

Jamieson, A. 2012. Tell Ahmar III. Neo-Assyrian Pottery from Area C.

Kazenwadel, B. 1995. Lidar Höyük: die hellenistische und römische Keramik. Dresden.

Kenrick, P. M. 2009. On the Silk Route: imported and regional pottery at Zeugma.

Kenrick, P. M. 2013. Pottery other than transport amphorae. Excavations at Zeugma.

Özbal, R. 2011. The chalcolithic of southeast Anatolia. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia.

Özbal, R., F. Gerritsen, B. Diebold, E. Healey, N. Aydın, M. Loyet, F. Nardulli, D. Reese, H. Ekstrom & S. Sholts 2004. Tell Kurdu Excavations 2001. Anatolica, 30, 37-108.

Özgen, E., B. Helwing, A. Engin, O. Niewenhuyse & R. Spoor 1999. Oylum Höyük 1997-1998. Die spätchalkolithische Siedlung auf der Westterrasse. Anatolia antiqua. Eski Anadolu, 7, 19-67.

Pearce, J. A. 2000. The Late Chalcolithic sequence at Hacinebi Tepe, Turkey. Chronologies des pays du Caucase et de l’Euphrate aux IVe-IIIe millénaires. From the Euphrates to the Caucasus: Chronologies for the 4th-3rd millennium B.C. Vom Euphrat in den Kaukasus: Vergleichende Chronologie des 4. und 3. Jahrtausends v. Chr. Actes du Colloque d’Istanbul, 16-19 décembre 1998., Varia Anatolica, 115-143.

Venturi, F. 1998. The Late Bronze Age II and Early Iron Age Levels. In: Mazzoni, S. M. C. a. S. (ed.) Tell Afis (Siria). Scavi sull’acropoli 1988-1992. 123-162.Pisa.

Table I—Survey Chronology

Period | Approximate dates | Key types and sites |

Paleolithic-Mesolithic | c. 100,000-10,000 BCE | KM 43, KM 1? |

Early Neolithic | c. 10,000-6500 BCE | KM 1?, KM 134, KM 70, 8, 67 red washed, burnished, incised wares |

Halaf-Ubaid | c. 6500-4200 BCE | KM 97 Halaf plain, painted, bichrome, small Ubaid plain and painted wares |

Local Late Chalcolithic | c. 4200-3200 BCE | KM 133, KM 214 Coba bowls; ‘funnel- necked’ jars; thickened band rims, linear incised ware, ledge-necked jars, “late bichrome” |

Early Bronze Age | c. 3100-2200 BCE | KM 555, KM 21 Brittle orange wares including beaded rims, bowls, incised wares, stemmed dishes and fine buff-corrugated wares |

Middle Bronze Age (EB/MBA and MBA) | c. 2200-1550 BCE | KM 2, KM 225, KM 173, plain simple carinated cups and bowls, combed grey ware, cook pot ware with calcite temper |

Late Bronze Age | 1500-1200 BCE | KM 48, drab ware, deep bowls, cooking pot ware with shell temper, |

Iron Age EIA=12-900 BCE MIA =900-550BCE LIA=550-333 BCE) | 1200-333 BCE | EIA painted wares; M-L IA KM 3, 80, thickened rim open forms, craters, coarse ware with heavy thickened rims, large finger impressed bands |

Hellenistic-Late Roman | 332 B.C-300 CE | KM 97, 78, 109, 196, 121 Hellenistic painted, Hellenistic fine wares, Terra sigillta, amphorae, rope impressed wares |

GAP | ||

Early Islamic 637-938 CE Middle Islamic 938-1337 CE Late Islamic 1337-1918 CE | 637-1918 CE |

| Descriptive Attribute | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| Creator Vocabulary: DCMI Metadata Terms (Dublin Core Terms) | Elizabeth Carter Vocabulary: Domuztepe Excavations |

| Subject Vocabulary: DCMI Metadata Terms (Dublin Core Terms) |

|

Explore Project Data

No records

Records associated with this project have yet to be indexed. These records are still in preparation and not yet fully published.

Suggested Citation

Elizabeth Carter. (2025) "Kahramanmaraş Survey". Released: 2025-02-17. Open Context. <https://opencontext.org/projects/ca4f4719-f2a5-4119-99fa-b04573c8929a> DOI: https://doi.org/10.6078/M7CC0XTH

Editorial Status

●●●○○Copyright License

To the extent to which copyright applies, this content

carries the above license. Follow the link to understand specific permissions

and requirements.

Required Attribution: Citation and reference of URIs (hyperlinks)